Avian Influenza outbreaks in Northern California have consumers asking where the disease came from and how dangerous it is to people…

Dr. Michael Payne, Western Institute for Food Safety and Security, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis.

The tight-knit agricultural community of Sonoma County, California was shaken in late November with the detection of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, HPAI, on two commercial farms.

This deadly, easily spread strain of “Bird Flu” can sweep through flocks, killing tens of thousands of birds in a matter of days. The current outbreak, which began in early 2022 and circulated primarily in the Midwestern U.S., has resulted in the death of more than 86 million chickens and turkeys.

There are currently no effective vaccines or treatments available for this virus strain. Because the virus it is so easily spread by wild birds, foot and vehicle traffic, infected farms are depopulated; the flock is euthanized to eliminate the source of the outbreak. Tragically, this has been the only option for the two Sonoma County flocks, with some quarter million ducks and hens euthanized by State and Federal authorities.

Where does Avian Influenza come from?

The University of California, through its Western Institute for Food Safety and Security, WIFSS, produced an informative video primer on Avian Influenza for poultry producers. As described in the video, strains of Avian Influenza (abbreviated as AI) are typically introduced into the U.S. from wild birds migrating along the East Asian Flyway, coming in contact with wild birds using the North American flyways.

Customized, effective Biosecurity Plans are the best defense.

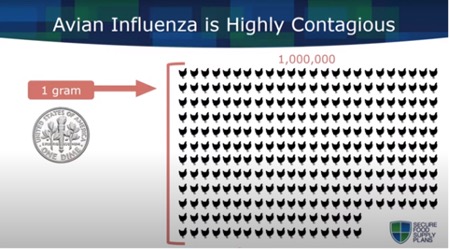

With just a small amount of dander, used bedding or a few feathers capable of carrying the virus, the primary defense against disease entry into a flock is the owner’s biosecurity practices. Each farm’s biosecurity plan will be unique depending on the farm’s location, management and facilities.

WIFSS at the University of California in concert with the California Department of Food and Agriculture is developing a biosecurity training website for small and medium sized poultry operations. Using videos, fact sheets, and plan templates, the website walks producers through the process of developing a biosecurity plan which meets standard requirements. Topics such as vehicle disinfection, personnel training, facility mapping, manure and mortality management are addressed in individual modules.

In addition to this website, WIFSS is working with local community colleges to integrate educational units on on-farm biosecurity into existing courses for undergraduate and high school agriculture and animal science students. The goal of this project is to train future farmers, biosecurity specialists, veterinarians, and government regulators on the importance of biosecurity for the protection of animal health and the security of our food system. It is critical that the industry be staffed with professionals who know how to evaluate farm premises, identify potential risks and hazards, and who are able to formulate mitigations strategies to effectively counter those identified risks and hazards.

Visitors (authorized or unauthorized) represent a risk…

Biosecurity practices, followed not only by employees but by visitors as well, are essential in protecting the flock. Visitors can carry the AI virus on their shoes or clothes from their own backyard hens, from local swap meets or farmers markets. Someone who has been hunting wild birds recently can carry contaminated feather down or dander on their jackets or hats. Foreign visitors, particularly from other countries experiencing AI outbreaks, represent a significant risk.

A common biosecurity practice is to have visitors fill out a questionnaire detailing other countries or farms they have recently visited and what contact they have had with commercial poultry or wild birds. High-risk visitors may be asked to return at a later date in new or freshly laundered clothing. Regardless of their history visitors may be asked to change into coveralls and boots owned by the farm and which are cleaned and disinfected after each use.

Similar to authorized visitors, unauthorized visitors represent a very real the risk of AI introduction to a farm. Hunters’ trucks, criminals stealing product or equipment or activist trespass all have the potential to carry the AI virus from an infected property to an uninfected property.

State and federal animal health and law enforcement officials will consider these risks during outbreak investigations.

Risk to humans?

Only in the rarest of circumstances has HPAI been shown to cause disease in humans. Typically, these disease transmissions involve prolonged, extremely close contact with high-risk birds such as in live markets or depopulation sites.

The CDC has been monitoring the health of more than 6,550 people exposed to the predominant type of HPAI circulating in the U.S., an H5N1 strain. Only one case of human infection in the U.S. has been identified in the U.S., in a depopulation worker who reported fatigue for several days and who has since recovered.

Human-to-human transmission of the AI virus has not been conclusively confirmed, and only a handful of potential cases have been reported worldwide. If or when such transmission does occur, it appears to be self-limiting. No human-to-human transmission has been reported in the current U.S. outbreak.

Food safety risk?

During an AI outbreak, positive farms are quarantined, depopulated, disinfected and tested for residual virus. Egg or poultry products from positive farms are not permitted to enter the food chain. Risk assessments performed by USDA and the FDA conclude that it is impossible for properly prepared food to transmit the virus to humans. Proper cooking inactivates the virus.

Editor’s Note: Dr. Payne informed us that the current outbreaks of HPAI in the United States has not changed his personal buying habits related to house-hold eggs, chicken sandwiches or Christmas turkey.